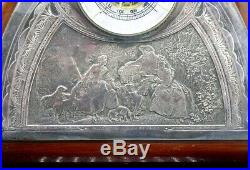

WOOD CASE FRENCH BAROMETER Made in GERMANY PLAISIRS CHAMPETRES FARM SCENE Face. THIS MONTH, WE ARE PLEASED TO OFFER MANY FINE ANTIQUE AND COLLECTIBLE ARTIFACTS AND RARITIES FROM MISSISSIPPI AND LOUISIANA ESTATES AND PRIVATE COLLECTIONS. AN ARCHED WOOD CASE, PERHAPS WALNUT, MEASURES 7.5″ WIDE AND STANDS 6.25″ TALL AND AROUND 1 DEEP, SET WITH A STRIKING, INTRICATELY DETAILED RURAL FARM SCENE FEATURING BAS-RELIEF ELEMENTS, ETCHED AND ENGRAVED DESIGNS AT CENTER, A YOUNG MAN, PERHAPS HOLDING A POULTRY CAGE, SEATED ALONGSIDE A MAIDEN, WITH A SHEPERDESS HOLDING A STAFF, TENDING SHEEP… A DOG RESTS TO THE GROUND. AT LOWER CENTER, ENGRAVED LETTERING RELATES A TITLE REALTIVE TO THE SCENE. TRANSLATING TO ENGLISH AS PASTORAL OR RURAL PLEASURES. A FRENCH ARTIST, ANNE-PHILIBERTE COULE, BORN IN 1736, PRODUCED AN ENGRAVING WITH THIS TITLE, NOW HOUSED IN A COLLECTION AT THE INDIANAPOLIS MUSEUM OF ART. ATOP, A FRAMED BAROMETER FEATURING BEVELED GLASS TO THE FACE, ALONG WITH VARIOUS WORDING TO THE DIAL, IN FRENCH, RELATIVE TO WIND, RAIN, STORMS AND OTHER ELEMENTS OF THE WEATHER. TO THE REAR, A SILVER PATINA METAL HINGED EASEL IS MOUNTED. THE METALLIC ELEMENTS ARE LIKELY SILVERPLATE, BUT EXHIBIT TRAITS RELATIVE TO STERLING. HISTORY OF THE BAROMETER. A barometer is an instrument used to measure atmospheric pressure. It can measure the pressure exerted by the atmosphere by using water, air, or mercury. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Numerous measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis to help find surface troughs, high pressure systems, and frontal boundaries. Although Evangelista Torricelli is universally credited with inventing the barometer in 1643, two other noteworthy efforts must be cited. Historical documentation also suggests Gasparo Berti, an Italian mathematician and astronomer, unintentionally built a water barometer sometime between 1640 and 1643. French scientist and philosopher Rene Descartes described the design of an experiment on atmospheric pressure determination as early as 1631, but there is no evidence that he built a working barometer at that time. On July 27, 1630, Giovanni Batista Baliani wrote a letter to Galileo Galilei about the explanation of an experiment he had made in which a siphon, led over a hill about twenty-one meters high, failed to work. Galileo responded with an explanation of the phenomena: he proposed that it was the power of a vacuum which held the water up, and at a certain height (in this case, thirty-four feet) the amount of water simply became too much and the force could not hold any more, like a cord that can only withstand so much weight hanging from it. Galileo’s ideas reached Rome in December of 1638 in his Discorsi. Rafael Magiotti and Gasparo Berti were excited by these ideas, and decided to seek a better way to attempt to produce a vacuum than with a siphon. Magiotti devised such an experiment, and sometime between 1639 and 1641, Berti (with Magiotti, Athanasius Kircher and Nicolo Zucchi present) carried it out. Four accounts of Berti’s experiment exist, but a simple model to his experiment consisted of filling a long tube with water that had both ends plugged up, then placing the tube into a basin already full of water. The bottom end of the tube was opened, and the water that had begun inside of it poured out of the bottom hole into the basin. However, only part of the water in the tube flowed out, and the level of the water inside the tube stayed at an exact level, which happened to be thirty-four feet, the exact height Baliani and Galileo had observed that was limited by the siphon. What was most important about this experiment was that the lowering water had had left a space above it in the tube which had had no intermediate contact with air to fill it up. This seemed to suggest the possibility of a vacuum existing in the space above the water. Evangelista Torricelli, a friend and student of Galileo, dared to look at the entire problem from a different angle. In a letter to Michelangelo Ricci in 1644 concerning the experiments with the water barometer, he wrote. Many have said that a vacuum does not exist, others that it does exist in spite of the repugnance of nature and with difficulty; I know of no one who has said that it exists without difficulty and without a resistance from nature. I argued thus: If there can be found a manifest cause from which the resistance can be derived which is felt if we try to make a vacuum, it seems to me foolish to try to attribute to vacuum those operations which follow evidently from some other cause; and so by making some very easy calculations, I found that the cause assigned by me (that is, the weight of the atmosphere) ought by itself alone to offer a greater resistance than it does when we try to produce a vacuum. It was traditionally thought (especially by the Aristotelians) that the air did not have lateral weight: that is, that the miles of air above us don’t weigh down on the air at our level. Even Galileo had accepted the weightlessness of air as a simple truth. Torricelli questioned that assumption, and instead proposed that the air had weight, and that it was the weight of the air (not the attracting force of the vacuum) which held (or rather, pushed) up the column of water. He thought that the level the water stayed at (thirty-four feet) was reflective of the force of the air’s weight pushing on it (specifically, pushing on the water in the basin and thus limiting how much water can fall from the tube into it). In other words, he viewed the barometer as a balance, an instrument for measurement (as opposed to merely being an instrument to create a vacuum), and because he was the first to view it this way, he is traditionally considered the inventor of the barometer (in the sense in which we use the term now). Due to rumors circulating within Torricelli’s gossipy Italian neighborhood, which included that he was up to some form of sorcery or witchcraft, Torricelli realized he had to keep his experiment more secretive, or run the risk of being arrested. He needed to use a liquid that was heavier than water, and from his previous association and suggestions by Galileo, he deduced by using mercury, a shorter tube could be used. With the use of mercury, then called “quicksilver”, which is about 14 times heavier than water, a tube only 32 inches was now needed, not 35 feet. In 1646, Blaise Pascal along with Pierre Petit, had repeated and perfected Torricelli’s experiment after hearing about it from Marin Mersenne, who himself had been shown the experiment by Torricelli toward the end of 1644. Pascal further devised an experiment to test the Aristotelian proposition that it was vapors from the liquid that filled the space in a barometer. His experiment compared water with wine, and since the latter was considered more’spiritous’, the Aristotelian’s expected the wine to stand lower (since more vapors would mean more pushing against the liquid column). Pascal performed the experiment publicly, inviting the Aristotelians to predict the outcome beforehand. The Aristotelians predicted the wine would stand lower. However, Pascal went even further to test the mechanical theory. If, as suspected by mechanical philosophers like Torricelli and Pascal, air had lateral weight, the weight of the air would be less in higher altitudes. Therefore, Pascal wrote to his brother-in-law, Florin Perier, living near the mountain called the Puy de Dome, requesting that the latter perform a crucial experiment. Perier was instructed to take a barometer up the Puy de Dom and make measurements along the way of how high the column of mercury stood. He was then to compare it to measurements taken at the foot of the mountain to see if those measurements taken higher up were in fact smaller. In September of 1648, Perier carefully and meticulously carried out the experiment, and found that Pascal’s predictions had been correct. The mercury barometer stood lower the higher one went. NO FIRST CLASS INTERNATIONAL PARCEL. The item “WOOD CASE FRENCH BAROMETER Made in GERMANY PLAISIRS CHAMPETRES FARM SCENE Face” is in sale since Sunday, May 17, 2020. This item is in the category “Antiques\Science & Medicine (Pre-1930)\Scientific Instruments\Barometers”. The seller is “ponyboynol” and is located in New Orleans, Louisiana. This item can be shipped worldwide.